The burial ship from the Viking Age contained a unique collection of wooden artefacts. Many of them were preserved with alum, which nowadays is causing serious problems.

The Oseberg burial mound was discovered in 1903 near Tønsberg (100 km southwest of Oslo, Norway). It consisted of a Viking ship, numerous wooden and metal artefacts, textiles and even sacrificed animals used as offerings to the two buried women. Amongst other things, the find includes a rich collection of carved wooden objects (e.g., ceremonial wagon, sledges and animal head posts), kitchen and shipping equipment, and furniture. The burial conditions preserved these wooden artefacts through impregnation with groundwater and the creation of an low-oxygen environment; the wood was therefore waterlogged.

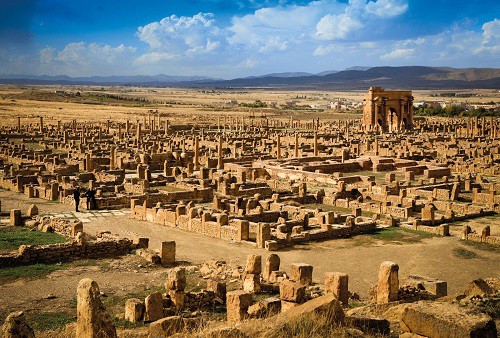

Archaeological wood artefacts from the Oseberg find (left, animal head post; right, kitchen equipment) exhibited at the Viking Ship Museum, Norway. Photo: KHM, UiO.

Read more about the Oseberg find at the the Musuem of the Viking Age’s website.

Conservation

At the time when the excavations were carried out, numerous wooden objects had to be restored and conserved. The objects had fallen into pieces and some of them were highly deteriorated, due to the weight of the stone and turf layers covering the ship burial and biological decay. Furthermore, the water inside the wood had to be removed to avoid further biological degradation. Depending on the wood from which the objects were made, they had to undergo different conservation processes in order to be preserved. Artefacts made of wood like oak, ash, pine and yew (e.g. the oak Viking ship) were the best preserved ones. For these objects, the conservation procedure was relatively easy and uncomplicated; the wooden fragments were mainly air-dried. However, the Oseberg find also contained extremely fragile objects that required consolidation before drying; otherwise the wood would shrink and/or collapse. This included objects with fine carvings (e.g., animal head posts) and/or made of maple and birch wood (e.g., sledges and parts of the wagon). The poor condition of these objects led to the use of a particular conservation treatment – the alum treatment.

Finely carved Gustafson’s sledge exhibited at the Viking Ship Museum, Norway. Photo: KHM, UiO.

Alum treatment

At the beginning of the 20th century, conservation methods for treating wet archaeological wood were limited. The alum conservation method was developed in Denmark in the mid-1800s and remained in use until the 1950s; it was mainly used in Scandinavia but has also been applied to other collections worldwide. As the method gave seemingly good results in stabilizing the wood before drying, it was chosen to conserve the most deteriorated wooden objects from the Oseberg find. Thousands of fragments were treated with alum, resulting in approximately 200 objects after reconstruction.

Testing the alum treatment on fragments from the Oseberg find in the early 1900s; the left fragment is alum-treated, the middle fragment is still wet and the right fragment shows the extent to which the wood shrinks without treatment. Photo: KHM, UiO.

Conservator Anna Rosenqvist treating one of the animal head posts from the Oseberg find. Photo: KHM, UiO.

The alum method entailed immersing the waterlogged wooden fragments in a concentrated solution of alum (potassium aluminium sulphate), heated to 90 °C to increase its solubility in water. The salt penetrated into the surface of the wood and replaced the existing water; alum’s recrystallization process supported the outermost surface of the wood and reduced shrinkage during drying. However, alum was not able to penetrate in depth, resulting in a weak innermost region of the wood.

Fun fact: After treating one animal head post with alum the carved surface details became blurry. The conservators decided to preserve the remaining posts in water until a better solution could be found (which was almost 50 years later). These objects were then immersed with tertiary butanol and freeze-dried.Re-construction

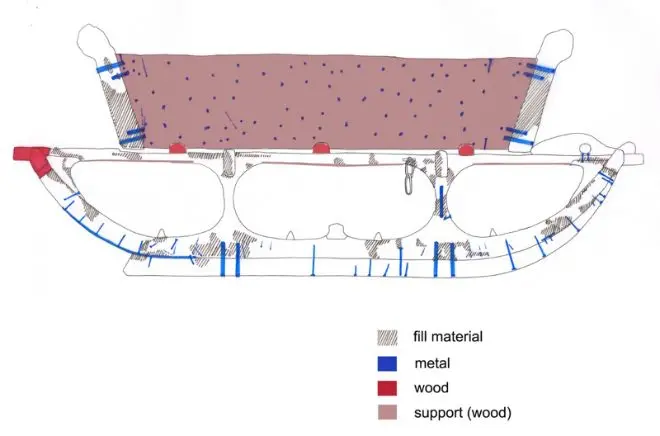

During the re-construction phase, the dried alum-treated fragments were coated with linseed oil and mounted together using metal pins, screws and adhesives. Some missing pieces were replaced with fresh wood and/or filled with putties. To ensure that the entire structure would remain intact, the objects were coated with several layers of lacquer. The objects currently on display at the Viking ship Museum were coated once again with an artificial resin in the 1950s.

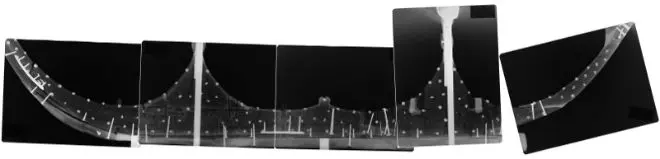

X-ray of the Fourth sledge runners, showing metal materials used during reconstruction (e.g., screws and metal plates; see white areas). Photo: KHM, UiO.

Deterioration

In the 1990s damage to a number of wooden objects from the Oseberg find was observed (e.g., ornamented sledges and wagon). The various elements used during conservation had made the artefacts too complex and heavy; the wooden structure had become fragile and deteriorated. Furthermore, the metal joiners used during restoration had become loose and parially corroded; the objects’ structures could no longer be supported. Closer examination revealed that only the alum-treated objects suffered from severe deterioration, leading to the assumption that the alum treatment was the cause; similar observations were simultaneously made in other Scandinavian collections containing alum-treated objects.

Deterioration of alum-treated wood from the Oseberg find (crack on Gustafson’s sledge). Photo: KHM, UiO/Kirsten Helgeland.

And what now?

It is crucial to find a solution for this problem; the degraded wooden artefacts have to be re-conserved in order to maintain them for future generations. This implies understanding the mechanisms involved in the degradation of wood and requires a broad knowledge of wood science, wood conservation, materials science and chemistry.

When studies on alum-treated wood started in 2007, the researchers could only rely on contemporary written sources (e.g., Conservation’s laboratory journal and Publication of the Oseberg finds – 1917, Vol. 1). Since this information was fairly inaccurate and similar problems have arisen in other waterlogged wood collections, focus was directed toward current research on archaeological wood. Studies carried out in Italy (Pisa project), Sweden (Vasa project) and Denmark provided information about the composition of wood after degradation, the influence of metal ions and re-conservation methods for alum-treated wood.

However, when developing new conservation materials and re-treating archaeological wood artefacts, one has to take into account the complexity of the objects and the reactions that occur; the different materials used during conservation/re-construction can interact with each other and with the new materials. Furthermore, many objects from the Oseberg find differ significantly from other collections; the most deteriorated objects were only treated with alum (no glycerol additives) and many of them have been restored to such an extent that deconstructing them would cause irreversible damage. Additionally, many of them have complex surface carvings, which are one of their most important features and therefore should not be lost.

Materials used during restoration of the Fourth sledge, including metals, fillers and fresh wood (see colors). Photo: KHM, UiO.

It is therefore important to discover the secrets behind the Oseberg objects and understand the composition and behaviour of alum-treated wood in order to prevent further decay of these valuable artefacts.